Translation of the article which originally appeared in the Russian language periodical in 2004.

Ireland, they say, has the honour of being the only country which never persecuted the jews. Do you know that? No. And do you know why?

He frowned sternly on the bright air.

— Why, sir? Stephen asked, beginning to smile.

— Because she never let them in, Mr Deasy said solemnly.

Ch. 2: Nestor

One day, while looking through a literary events calendar, I came across an unfamiliar entry – Bloomsday. It turned out, it refers to Leopold Bloom, the main character in the James Joyce novel “Ulysses.” Bloomsday is celebrated annually by the world literary community on June 16, and commemorates the life of James Joyce. June 16, 1904 is also the day the events of the novel take place. And here, I first got an idea to celebrate this day in Dublin, and with the centennial celebration approaching, I began to prepare to celebrate in my special way, with an art exhibition.

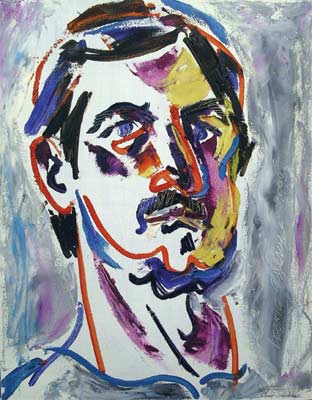

Portrait of James Joyce by Leonid Osseny

I started studying the novel, and to better navigate the labyrinth of events, I began to sketch episodes and characters, working from drawing to drawing to unravel the elements of the plot. To an unprepared reader, my advice would be to abandon any hope of reading the text from start to finish. A distinguished professor and scholar of Joyce, John Bishop, put it this way: “Only after I turned the last page of the book did I understand it is time to return to the first one and start from the beginning.”

I suggest reading the book in both English and Russian simultaneously, and note how the translator interprets some of the more difficult passages in the text; you should not rush – this book is not meant to be read in one week or even a month. When Joyce was told that “Ulysses” was too complicated, he replied “as it should be, it took me eight years to complete it.”

Ireland produced such imminent writers as Jonathan Swift, Bernard Shaw and Oscar Wilde. James Joyce occupies a special place among them, in that he left his country for good in 1904, and then brought her a worldwide acclaim.

Joyce’s Grandniece and nephew with Leonid Osseny in Dublin 2004

In the United States “Ulysses” came out only in 1934, it was banned by authorities on the count of being “lewd”, and only after a ruling by the court was it allowed to be published. I have the first American edition of the book. I inserted my illustrations among the pages, and at the James Joyce symposium, I jokingly asked some experts to provide an estimate of its value.

When on June 16 of this year, the world literary community celebrated the Centennial of the Leopold Bloom’s “Odyssey”, the largest celebration took place in Dublin. I was honored by the symposium committee to exhibit my artwork during the conference.

The symposium included more than 800 participants representing 39 countries. Still, not a single guest from the former Soviet Union, and even though I am now an American citizen, I would like to think, I also represented Belarus, a country similar to Ireland in its historical development with the loss of independence and national language.

Flyer for the Symposium

The presentations at the symposium covered a wide range of topics, from the planetary alignments on June 16, 1904, to why Leopold Bloom did not divorce his wife Molly after discovering her infidelity. The participants even went so far as to suggest a urination Olympiad, inspired by the scene described in the novel.

My exhibition took place in a large auditorium at the National College of Ireland, with the artwork creating a setting for the presenters. In addition to the illustrations for the book, I created a number of storyboards connecting the two creative geniuses of the 20th century – Sergei Eisenstein and James Joyce. Eisenstein said: “In my films I think and reason in the same way Joyce does in literature, namely through the device of “Inner Monologue.” And it is this understanding of the ‘Inner monologue’, which for me, provides a key to reading the novel. My artistic education in the field of composition was informed by the creative work of Eisenstein, which itself was based on this mysterious idea of the “Inner Monologue.”

TWO MEN OF GENIUS DIVIDED BY REVOLUTION BUT UNITED UNDER THE ‘INNER MONOLOGUE’

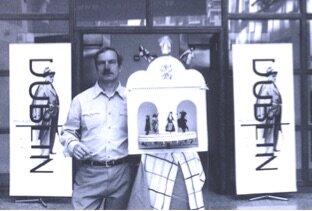

I brought with me to the conference a small ‘Batleika’, a Belarusian folk puppet theater,and entertained the delegates with a puppet show, while on stage, I set up a banner with the palindromes from “Ulysses” - “MADAM, I’AM ADAM” and “ABLE WAS I ERE I SAW ELBA”. At the top of the stage was a quote from Shakespeare: “All the World’s the Stage”, which fit with my ‘BATLEIKA’ quite well.

Leonid Osseny with Batleika – Puppet Theater

But most importantly, at the conference I was able to grasp things “unseen” in the novel. I saw the “Joyce Tower”, the cliffs, and the frigid Irish Sea, beyond the sea, at a hundred miles or so, the country of England, which released Ireland from its stronghold only in 1928. During the study of the book, I got an urge to purchase an authentic Irish coin of 1904 mint. At the coin shop, the proprietor shrugged his shoulders and said he had no such coins, since the national currency did not come into circulation until Ireland’s independence in 1928. The year when the “Irish Harp” became one the symbols of national identity.

Joyce Tower, Sandycove, Co. Dublin

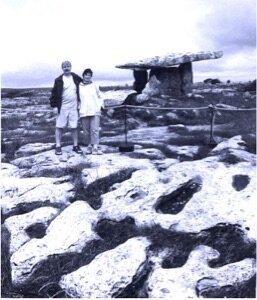

Symposium allowed me to witness this wondrous country, with the ocean gales sweeping across its surface with hardly a pause, and polished rocks along the shore reminiscent of sea foam, one can forgive for mistaking where the ocean ends and the land begins.

Leonid and Sonya Osseny in Ireland 2004

And how did James Joyce see Ireland through the eyes of his novel’s hero Leopold Bloom in the year 1904? In terms of architecture Dublin has changed very little.

O’Connell Street in Dublin

Historical monuments that go as far back as the 12th Century have undergone extensive renovations, and now are well integrated into the fabric of the city. At the beginning of the 20th century, and specifically year 1904, the city had only six automobiles trying to negotiate streets teeming with horse drawn carriages and a handful of streetcars. The detail with which Joyce recreates Dublin on June 16, 1904 is remarkable.

College Green and Bank of Ireland

Leopold Bloom’s path through the city is recorded with such accuracy that even now, a hundred years later, we can precisely retrace his steps. On the streets, you can find bronze placards pointing in the direction of the journey and indicating what happened there on “Bloomsday”.

At the exhibition, I struck up a conversation with a Joyce scholar. I asked her what she thought of my work; she responded she liked the images, especially the portrait of Bloom’s wife Molly. Except, she noted, in the book, she had brown eyes. I said I imagined her eyes reflecting the sea. When I returned to Chicago, and reread passages from the book, I was delighted to find this description of Molly: “A seachange this, brown eyes saltblue. Seadeath, mildest of all deaths known to man. Old Father Ocean.”

Portrait Molly by Leonid Osseny

At the symposium I met two Irish ladies – mother and a daughter. I was surprised to find out the mother was 95 (!) years old, yet she is still a devout follower of Joyce, actively staying in touch with her likeminded friends. She calls herself a “Joyceaness”.

I would like to think, once a person steps on the path of reading and discovering Joyce’s novels, he continues the journey for the rest of his life.

Gabrielle Veale -Daughter, Sonya Osseny and Eileen Veale- Mother Dublin 2004.

Leonid Osseny, Chicago 2004